The Rationale and Relevance of Our Sonship

This teaching is from Session 1 of our Men’s Retreat on September 19, 2025. Audio is available upon request.

On a blank page, draw a line down the middle, on the left side, up at the top, write “Who are you?” And then under it, answer that question. Describe who you are in the first person: “My name is [your name]” and say who you are.

* * *

I believe that our topic we’ll talk about in this session and tomorrow’s session is the most important thing we could think about as men because it’s foundational to everything else.

And I feel a measure of trepidation with it … We’re gonna go some places tonight and tomorrow that might be uncomfortable for us, and in that moment of discomfort you might be tempted to put up a wall inside and turn off your hearing, or get cynical and check out … but I want to ask you now that you try hard not to do that. Because God has something for us in necessary discomfort. And that’s part of the pathway for us to embrace our true selves. Which is my goal for us.

I have two parts tonight:

Make a biblical case for the importance of sonship

Show you why embracing your sonship is essential

The rationale and relevance of our sonship …

The Biblical Case

Let’s turn to Luke 15. Luke 15:11–32 is our passage for the weekend, and it’s arguably the most popular story Jesus ever told. The New Testament scholar Peter Williams has written a book that argues for the historical classification of Jesus as a genius, and he uses this story in Luke 15 as the case study to show how brilliant Jesus was as a teacher and storyteller. There are layers of wonder here. So let’s read it.

Luke 15:11-32,

And he said, “There was a man who had two sons. 12 And the younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of property that is coming to me.’ And he divided his property between them. 13 Not many days later, the younger son gathered all he had and took a journey into a far country, and there he squandered his property in reckless living. 14 And when he had spent everything, a severe famine arose in that country, and he began to be in need. 15 So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him into his fields to feed pigs. 16 And he was longing to be fed with the pods that the pigs ate, and no one gave him anything.

17 “But when he came to himself, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have more than enough bread, but I perish here with hunger! 18 I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. 19 I am no longer worthy to be called your son. Treat me as one of your hired servants.” ’ 20 And he arose and came to his father. But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him. 21 And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ 22 But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet. 23 And bring the fattened calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate. 24 For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’ And they began to celebrate.

25 “Now his older son was in the field, and as he came and drew near to the house, he heard music and dancing. 26 And he called one of the servants and asked what these things meant. 27 And he said to him, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fattened calf, because he has received him back safe and sound.’ 28 But he was angry and refused to go in. His father came out and entreated him, 29 but he answered his father, ‘Look, these many years I have served you, and I never disobeyed your command, yet you never gave me a young goat, that I might celebrate with my friends. 30 But when this son of yours came, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fattened calf for him!’ 31 And he said to him, ‘Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. 32 It was fitting to celebrate and be glad, for this your brother was dead, and is alive; he was lost, and is found.’ ”

This is God’s word.

Two Sons

Historically, this story has been called “The Parable of the Prodigal Son” — most English translations insert a heading that says that above verse 11. A lot of us are familiar with this story, but my hope is that we can look at it freshly tonight, starting with that first line of the story, in verse 11,

“And he [Jesus] said, ‘There was a man who had two sons.’”

Let’s do some inductive Bible study.

Answer some questions here looking at verse 11 …

What did the man have — what are they called? … Sons.

How many of them are there? … Two.

Two sons.

Now, let’s talk about the “two.” Because, again, the heading in my English Bible says “Prodigal Son” — singular — as if the story is about one son.

I just read this story to my youngest daughter the other night, in the Jesus Storybook Bible, and it was all about one son. A lot of times when we think about this story, we probably think about the one son. But, if we’re listening to Jesus, he tells us right away that this is a story about how many sons? … Two.

And notice especially that Jesus calls them “sons” (not brothers). This is important. A lot of times you might hear people refer to these two sons as brothers — we use the language of “younger brother” and “older brother” — but I want you to note that’s not how Jesus talks about them (The word “brother” is only used twice, in verse 27 and 32, about the father’s action and then in the voice of the father.) Because the focus of this story is not their brotherhood, but their sonship. This is a story about sons, which means our eyes are on their relationship to their father, not to one another. This is a story about a father, and he had “two sons.”

And when we read those two words it takes us into the depths of the Bible’s teaching, both diachronically and synchronically.

Diachronic Survey

Hang with me here: By diachronically, I have in mind a wide-lens view of the whole Bible’s teaching on a particular topic. This would be the question: What does the whole Bible say about sonship?

Here you go. Big claim: Sonship is the Bible’s most fundamental way to talk about who we are in Christ.

Sinclair Ferguson writes,

[That we are the children of God] lies at the heart of understanding the whole of the Christian life and all of the diverse elements in our daily experience. It is the way — not the only way, but the fundamental way — for the Christian to think of himself. Our self-image, if it is to be biblical, will begin here. God is my Father … (2)

Which raises the question: we all have some kind of self-image … it’s part of our human consciousness … we all see ourselves in some way … and so what is that?

I want you to think about this: How do you see yourself? When you imagine yourself in this world, what do you think? … Could it be more biblical?

Ferguson, again:

How important is sonship in biblical teaching? We can express its centrality abruptly but truly by saying: Our sonship to God is the apex of creation and the goal of redemption. (6)

J. I. Packer, in Knowing God, writes,

The revelation to the believer that God is his Father is in a sense the climax of the Bible, just as it was a final step in the revelatory process which the Bible records. (202)

He says,

You sum up the whole of New Testament teaching in a single phrase, if you speak of it as a revelation of the Fatherhood of the holy Creator. In the same way, you sum up the whole of New Testament religion if you describe it as the knowledge of God as one’s holy Father. If you want to judge how well a person understands Christianity, find out how much he makes of the thought of being God’s child, and having God as his Father. If this is not the thought that prompts and controls his worship and prayers and his whole outlook on life, it means that he does not understand Christianity very well at all. For everything that Christ taught, everything that makes the New Testament new, and better than the Old, everything that is distinctively Christian as opposed to merely Jewish, is summed up in the knowledge of the Fatherhood of God. “Father” is the Christian name for God. (200)

Muslims don’t call Allah their father. Jewish people don’t either. This truly is a distinctively Christian reality, and I believe it is more prevalent in the Bible than I have given it credit. I’ve been humbled the past few months as I’ve read and studied in view of tonight.

By God’s grace, I don’t think I’ve misunderstood Christianity, like what Packer says, but I will say that I’ve been convicted that I need to let the reality of sonship occupy its biblical prominence in my own thinking and teaching. I’ve been trying to do that — I’ve even revised how I think of Christian Hedonism, personally. Pastor John Piper made a slight biblical revision of the Westminster Confession, so in the same way, my slight biblical revision to Christian Hedonism is to say that “God, our Father, is most glorified in us, his children, when we are most satisfied in him.”

Our sonship is most likely a bigger deal in the Bible than we realize. 1 John 3:1,

“See what kind of love the Father has given to us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are.”

If we have the whole Bible in mind, diachronically, when we read “sons” in Luke 15:11 we ought to lean in and think This is a theme. This is big.

Synchronic Survey

And also, again, there are “two sons.”

Synchronically, we think about the Bible as a storyline, if we walk through the Bible from start to finish, we’ve seen some stuff about two sons before. Y’all ever heard the Bible talk about “two sons”?

Cain and Abel?

Isaac and Ishmael?

Jacob and Esau?

If you’re reading through the Bible and you get halfway through Genesis, you might think this whole book is gonna keep being about two sons.

Then, one layer beneath the “two sons” is the focus of what’s been called the “drama of the son.” (I first heard that phrase from Old Testament scholar Stephen Dempster.)

Beginning in Genesis 3:15, when God says that the seed of the woman will crush the head of the serpent, all eyes are on this seed. We’re looking for this son to be born.

And it’s doesn’t go great for the first two sons because one of them kills the other.

Noah’s sons were a mess.

Abraham is gonna have a lot of sons, but he jumps the gun on the first son, who ends up splitting because he doesn’t get along with the second son.

And then that second son, Isaac, has a younger son who tricks his older son for his birthright.

And Jacob has twelve sons, eleven of which conspire to kill the favorite son.

And by the time we get to Exodus, Pharaoh is trying to kill all the sons.

Elimelech’s two sons died.

But then from Boaz came the son Obed.

And Obed had a son, Jesse.

And Jesse had some bigger sons, but God chose the smallest one, David, who God promised would have a son to be king forever.

Brothers, the Bible is a book about sons.

That’s what the genealogy in Matthew 1 is saying. Remember: this is how the New Testament starts! Matthew summarizes the whole Old Testament in sons until we get to Jesus who is called, in Matthew 1:1, “the son of David, the son of Abraham.” Jesus is the Son of God, the Son of man, the “firstborn son among many brothers” (Romans 8:29).

And Jesus, the Son, told a story that started:

“There was a man who had two sons.”

So we’re listening to this. He’s got our attention, right?

Two Lost Sons

There are how many sons again? … Two.

And both sons are lost.

And we should have a clue about their lostness even before we even read the story, because this is the third parable that Jesus has told in a row in Luke 15. And all three of the stories are about lostness.

First, in Luke 15:1-7, Jesus tells the story of the lost sheep.

Second, in verses 8–10, Jesus tells the story of the lost coin.

The lost sheep is lost where? By leaving the flock and going out.

The lost coin is lost where? Where did the woman lose her coin? At home.

Then next you have a story a little longer than both those stories put together about a man who has two sons. The younger son is lost by leaving and going out. The older son is lost where? Home.

All that to say, I would submit to you that Luke Chapter 15, starting in verse 11, should be called “The Parable of the Two Lost Sons.”

There are two sons … and we’re going to see, they are two lost sons.

And that pretty much describes the manhood crisis in 21st century America.

We’re a country of lost sons.

Why It Matters

Now we’re talking relevance. I want to tell you why sonship matters for us, and to get there I’d like to zoom out and locate this talk within the greater context of our past topics related to masculinity. Going back to last summer, we talked about the pursuit of manhood — that, like manhood, living the Christian life is quest-oriented, and therefore being a Christian is the fulfillment of your manhood, and in no way contradicts it.

We talked about the importance of fraternal affirmation, of saying to one another “You are a man, act like one,” and we talked about masculine strength and agency. As a man, you are called to gladly assume sacrificial responsibility; to lead, provide, and protect for your family and others, even at a cost to yourself. And that means usefulness, we want to share our resources, skills, and wisdom.

Overall, the emphasis in all of that has been on our doing — which is appropriately masculine. Men, at large, are naturally doers. We are builders, fixers, achievers. We really like getting things done.

God made us this way, and it is good. This is why men bond better when we’re shoulder to shoulder, not face to face. This is why men loves teams and common goals, and why soldiers redeploy over and over again. Men are doers.

But often, whether we know it or not, our doing is motivated by wounds.

Now I’m going to use this word a lot — “wounds.” And I don’t want you to lose me on it. When I say “wounds” I have a broad definition. I’m talking about any kind of injury that has had a shaping effect on your person. It could include physical injury, but I’m thinking especially about mental and emotional wounds. And I just want you to know: every single one of us has these wounds. To be a man is to have these wounds. And every wound carries with it a message. But the typical response of men to our wounds is to hide them, rename them, or try to fix them ourselves.

That’s what is going on with the DO - HAVE - BECOME project (that I mentioned in the sermon from two weeks ago: “Jesus Is Different”).

We DO (x) in order to HAVE (y) so we can finally BECOME (z).

Part of being a man is to have some kind of wound in our being (z) — or really, a wound in our self-understanding of our being, our self-image. (And I think there’s something peculiar to men here, but for now suffice it to say: wounds in a man’s self-image is a fact of our fallen humanity. It’s part of a sin-tainted world.)

In different degrees, for every man, it’s difficult for us to embrace who we are, which is reflected in a pressure to keep proving ourselves as men. Again, we’re naturally doers, but we get this mixed up. We keep doing in order to have so we finally become (something different than what our wounds says). And we keep running that play over and over again … Do-Have-Become, Do-Have-Become, Do-Have-Become.

And the truth is, it gets exhausting. It gets especially exhausting when there’s insufficient affirmation, because affirmation is about being. It’s when an outside voice agrees with how you would dare to view yourself (different from your wound’s message). And men are famished for affirmation.

And there’s a little hack here your wife might figure out. If she wants you to finish that “Honey-Do List” then she ought to affirm the heck out of you. It goes like this:

“You work so hard for our family.”

“You are a good man.”

“Thank you for loving me so well.”

“You’re such a good dad.”

“I’d go anywhere with you.”

“I feel so safe with you.”

“I trust you with all my heart.”

Men, just imagine your wife saying these things to you. Just the thought makes that chest start swelling. And you wanna say to your wife: How can I help you today? Need me to do something? Give me a job!

Let me honor my mom for a minute. My dad, objectively, is a hard worker. He works in construction and I grew up with my dad coming home from work tired and his clothes filthy. I saw that, but also I heard my mom talk about how great a man my dad was. She told him. She told us kids. And you know what, I believed her. She was right.

Now, there’s a lot of places we can go here (a lot of tangents). For one, we can get into the powerful influence of women on men. It’s a real thing. But on the other side of that, part of the reason women are so influential on men is because of what we’ve been talking about — men have wounds in their self-understanding. Men are profoundly insecure.

And when the affirmation is not there — when men are not being affirmed — our doing starts to get strained and feel pointless. Because the Do-Have-Become project isn’t working. It’s not getting you where you want to go. This is what afflicts many men.

Men are doers, naturally, but in our brokenness, we think if we can just do enough, we can finally overcome the wounds in our being.

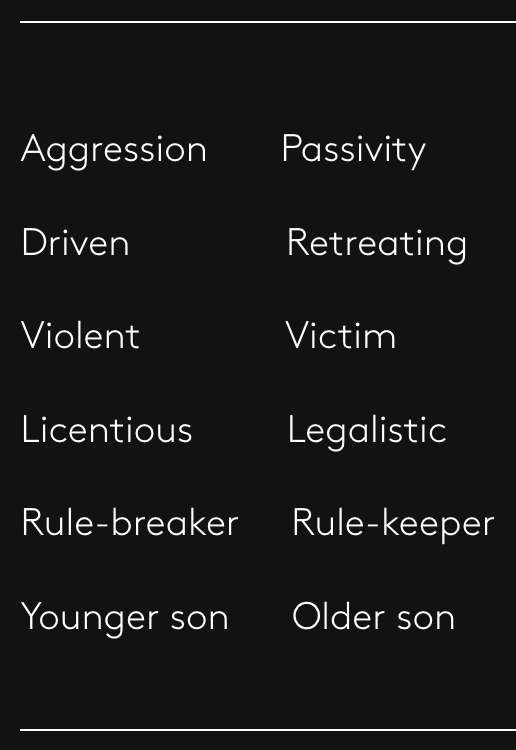

But doing, like that — wound-led doing / doing that chases becoming — typically gets manifest in two ways, aggression or passivity.

Think about this: what happens to many young men when they don’t have anything constructive to do?

They commit crimes or escape into videos games.

Seriously, this is a fact with countless men. Aggression or passivity. One writer puts it like this,

There are two basic options. Men either overcompensate for their wound and become driven (violent men), or they shrink back and go passive (retreating men). (John Eldredge, Wild at Heart, 68)

It can often be an odd mixture of both, but notice there is a dichotomy (it’s a helpful framework). At large, there are two different ways to go about our doing…

There are two ways … “There was a man who had two sons.”

Both sons are lost sons. I want to show you how their lostness plays out, first with the younger son. Back to Luke 15.

The Younger Son

The younger son, here we go, verse 12,

“And the younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of property that is coming to me.’ And he divided his property between them.”

And if you’re familiar with the story, you know that the younger son’s request would have been shocking. He is set to receive his inheritance once his father dies, but he asks for it upfront before his father dies, which would have been insanely disrespectful. It’s like he saying, I wish you were dead. I don’t want you, just the stuff you can give me.

But notice that last word in verse 12: “them.”

That means the younger son and the other son. See, in this culture, when a father died, his oldest son would receive a double portion of what the other children inherited (see Deuteronomy 21:17). If a father had two sons, two heirs, the oldest would receive two-thirds of the estate and the younger would receive one-third.

All that to say, the father “divided his property between them” means the older son comes out pretty well here. He got paid even better than the younger son. (That’s a little detail to keep in mind.)

But look what the younger does. Verse 13,

“Not many days later, the younger son gathered all he had and took a journey into a far country, and there he squandered his property in reckless living.”

“…far country” — he’s leaving home … And out there, in the far country, “he squandered his property in reckless living.”

“Squandered” and “reckless” are good translations. You could also say wasted and wild.

The younger son wasted all he had on wild living.

He’s unrestrained, off the rails. And we don’t have any more details than that. This is part of the brilliance of Jesus’s storytelling. He leaves a part to our imagination. The hearers/readers fill in that blank space with what they’d imagine to be wasteful and wild.

Whatever the details, it’s clear the younger son, in his wastefulness and wildness, made a mess of his life. He burned all his money. And then things go from bad to worse in verses 14-16:

“And when he had spent everything, a severe famine arose in that country, and he began to be in need. 15 So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him into his fields to feed pigs. 16 And he was longing to be fed with the pods that the pigs ate, and no one gave him anything.

The word “need” in verse 14 is intense. It means destitute. And then verses 15–16 describes how destitute looks: This younger son is now a servant, in a foreign land, and his job is to feed pigs (non-ideal job for a Jewish man). He was so destitute, that Jesus said he was longing to be fed with the pods that the pigs ate. He longed for pig slop, but “no one gave him anything.”

This is a nightmare. Now he’s been in the pit a long time, but now he’s found a certain part of the pit — he’s at rock-bottom. Now why? … Think about this.

Look back at verses 13–14 and tell me why he’s at rock-bottom …

Now, this is interesting … How we understand the reason for his being in the pit is telling. On one hand, he spent everything (his fault), but then also, a famine comes in the country he was in (not his fault). And then he began to be destitute.

So, if we’re paying attention to all the facts, and we’re reasonable, this younger son is at rock-bottom because of bad decisions and bad luck.

Facing the False Self

So the younger son is at rock-bottom. But then verse 17.

“But when he came to himself …”

That’s a literal translation. It’s the same way in the King James, and we get what it means. The NIV says he came “to his senses” but we get the literal. “He came to himself” is conversion language. He snapped out of something. And that raises a question. If he came to himself in verse 17, where was he in verses 13–16? Apparently not himself. So what do we call “not yourself”?

It’s your “false self.”

The false self is what we call the thing we construct with Do-Have-Become. It’s the self that is the result of your hard work, the thing you’re building toward it. And it’s insanely fragile. It’s as fragile as the thing you’re building it with (often affirmation and some gift or skill you have, the thing you think you’re good at).

Y’all ever seen the movie, The Natural? It’s a movie about male psychology. John Eldredge tipped me onto this.

Phenom baseball player, Roy Hobbs, is the greatest player to ever play. But a little secret to his success is this special bat he has. When he was in high school, a big tree in his front yard was struck by lightning and it fell, and he made a bat out of the tree … burned a lightning bolt in the bat and the words “Wonder Boy.” It’s the only bat he’s ever used.

Well, fast-forward, end of the movie, he’s in the biggest game of his life. This is where he can finally prove himself. Bottom of the ninth, two outs, his team is down 2-0 and he’s got two guys on base. First pitch, swing and miss. Second pitch, he belts one high, down the first base line, looks like a home run, but hooks foul. Down 0-2.

He comes back to the plate and his special bat, Wonder Boy, is snapped in two. He tells the bat boy to grab him another one.

Not only that, he steps back into the box, and on his stomach, there’s blood coming through his jersey … because an old gunshot wound from 20 years ago decides to tear open…

So he’s in this most critical moment of his life, his chance to prove himself — and this wound from his past presents itself, and the thing he’s counted on this whole time in his doing breaks apart. We call that a crisis, brothers.

One writer says,

“The truest test of a man, the beginning of his redemption, actually starts when he can no longer rely on what he’s used all his life. The real journey begins when the false self fails” (Eldredge, 100).

And a man’s false self will fail eventually by some crisis, either a circumstantial crisis or midlife crisis. Circumstantial is self-explanatory, it’s when your bat breaks. Something explodes and you realize what you’ve been doing doesn’t deliver like you hoped. Midlife crisis is a little more complex, but it’s something I’ve thought about because I turned 40 this past summer.

A midlife crisis happens because you realize that you pretty much are who you are. You’ve played Do-Have-Become long enough that things are pretty set. Who you are is who you are, what you’ve got is what you’ve got. Which leads many men into either despair or defiance.

In despair, we regret that we didn’t do more to become something better.

In defiance, we think we did do more to deserve better than what we’ve got, and so we go grab. We “see and take” … toys or women or control (through crazy big decisions). This is aggression.

It’s aggression or passivity. The False Self will fail.

For the younger son, it happened in verse 17.

The Maximus Moment

“He comes to himself” — which means he rejects the false self and he remembers who he is. Notice what he says … verse 17 …

“How many of my father’s hired servants …”

Who’s father? … My father.

How many of my father’s hired servants have more than enough bread, but I perish here with hunger! I will arise and go to my father [say it again, who’s father? … My father ], and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son. Treat me as one of your hired servants.”

This is semi-conversion. He recognizes, first, that he has a father. But then he thinks that his doing has disqualified him as a son (because, again, he’s been running Do-Have-Become). So he figures: I don’t deserve to be a son because of what I’ve done, but maybe he’ll let me be a servant.

So the younger son remembers he has a father, but he is too ashamed to call himself by the name his father has given him. He knows his only chance is going to his father’s home, even if it’s no longer his home.

The word “father” is used seven times in verses 16–22; we’re about to hear what the story is really about … Verse 20,

And he arose and came to his father. But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him.

And the son said to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son. … [look at this!]

But the father said to his servants [completely ignores what the son says], “Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet. 23 And bring the fattened calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate. [Here it is] 24 For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.’”

The father calls the lost man “my son” — which means the father declares the son to be what he knows he does not deserve. An undeserved declaration.

Brothers, that’s the gospel. We are who God our Father says we are.

Because we are united to Jesus, what God said of him, God says of us. God your Father says of you, “This is my beloved son in whom I am well-pleased.”

That is who you are. The whole Bible makes this case. But you gotta come home to it. It’s from here that we’re called to live. Not Do-Have-Become, but Be-Have-Do.

I am a beloved son of God / I have his riches in glory in Christ Jesus / I do everything in love for him and others.

This is fundamental for men. We have to remember who God our Father says we are.

We can learn something here from Gladiator, another movie about male psychology.

Russell Crowe plays Maximus, the protagonist. He was the commander of the Roman Army, and Marcus Aurelius, the old and frail emperor, had chosen him to be his successor. But before he could name Maximus as his successor, the emperor’s son, Commodus, kills his father and sentences Maximus to execution. Maximus escapes, goes back home to family, but only to discover that Commodus had murdered his wife and son and burned everything he owned. Then Maximus was captured by slave traders and sold as a gladiator. This is the pit. He’s close to rock-bottom. But it’s one fight after the other, and he’s winning, becoming a champion. Then he goes to Rome to perform in the Colosseum in front of Commodus who had made himself emperor. Maximus has a reputation from winning all these battles, but nobody knows who he is. He wears a helmet that covers his face. So he’s just called the Spaniard. But at the Colosseum he wins this amazing battle, and so Commodus comes down to the field to meet him. Here’s the dialogue:

Commodus says,

“Your fame is well deserved, Spaniard. I don’t believe there’s ever been a gladiator that matched you … Why doesn’t the hero reveal himself and tell us all your real name?”

Maximus is under his helmet-mask, just silent. Seething.

“You do have a name?”

Maximus goes,

“My name is Gladiator.”

He turns and walks away.

Commodus says,

“How dare you show your back to me?! Slave, you will remove your helmet and tell me your name.”

Maximus stops … then very slowly lifts his helmet …

“My name is Maximus Decimus Meridius;

Commander of the Armies of the North;

General of the Felix Legions;

loyal servant to the true emperor, Marcus Aurelius;

father to a murdered son; husband to a murdered wife;

and I will have my vengeance, in this life or in the next.”

One of the best movies scenes ever, and it’s instructive for men. Because we learn that Maximus has not been projecting a false self, but he concealed his true self until the moment demanded it. But even before this revelation, all that he’s been doing has been from his true self. He has embraced his identity, and his wounds are part of that. It’s in the short list of his self-understanding. His wounds are part of his story, but they don’t define who he is. He is Maximus Decimus Meridius.

Every man has to get here. We could call this “our Maximus moment” or we could call it “Coming home.” Because that’s what it is.

It’s what the younger son dared to do. It’s what we must do.

And I want to pick up here tomorrow with three points of application, but let’s end tonight going back to that page we started with. On the left side you answered the question, “Who are you?”

On the right side, at the top, I want you to write “Who God Says I Am” … and under it, write “beloved son of God.”